hyper-reV

1. Introduction

hyper-reV is memory introspection and reverse engineering hypervisor powered by leveraging Hyper-V. There is also a usermode component The project provides the following abilities for the guest - meaning the Windows operating system virtualized by Hyper-V - to: read and write to guest virtual memory and physical memory, translate guest virtual addresses to their corresponding guest physical addresses, SLAT code hooks (also known as EPT/NPT hooks), and hiding entire pages of physical memory from the guest. The fact that it leverages Hyper-V means that it will also work under systems protected by HVCI.

There is also a usermode component which serves as a kernel debugger.

2. Prior to boot

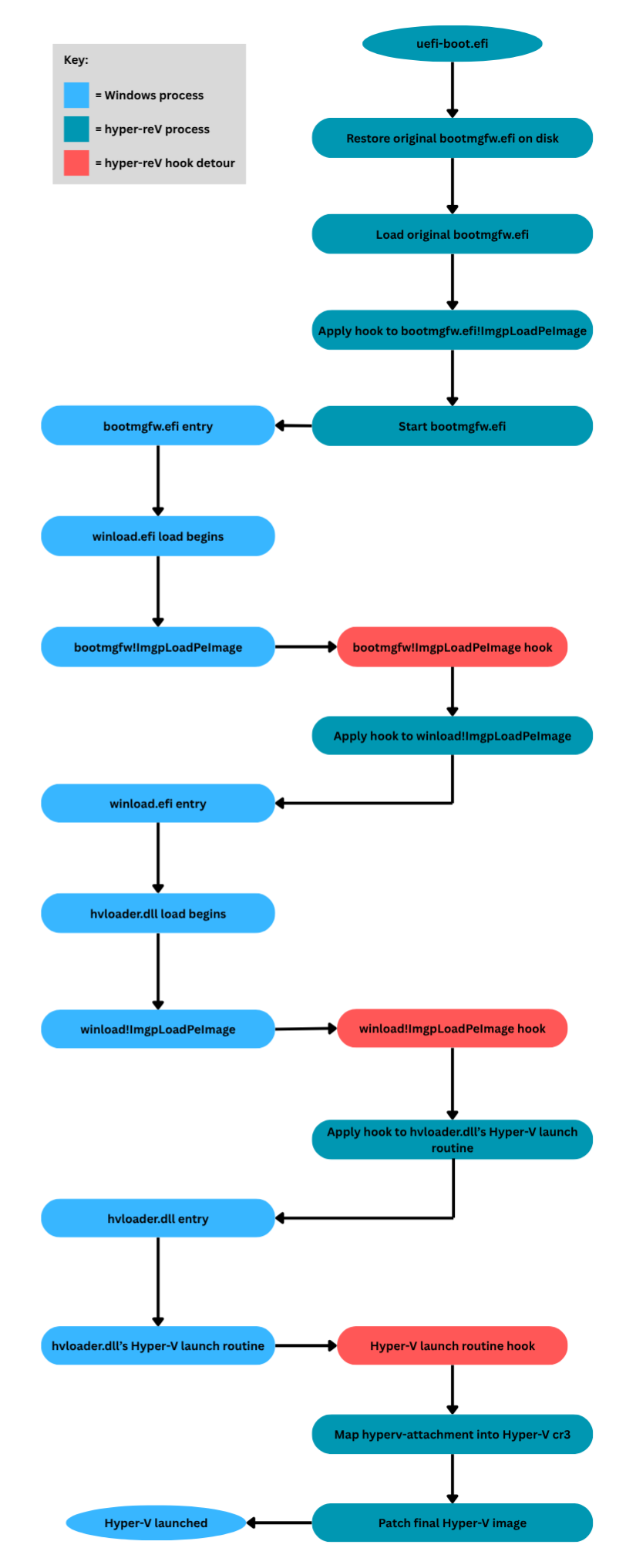

The ‘uefi-boot’ module is hyper-reV’s UEFI driver. A copy of bootmgfw.efi is made. The contents of bootmgfw.efi are then replaced with the ‘uefi-boot’ module so that it will be executed at the next boot. The hyperv-attachment (the module inserted into Hyper-V) is also saved on disk in the same directory as bootmgfw.efi.

3. Boot process

3.1. Restoration of bootmgfw.efi

Once the ‘uefi-boot’ module is started, the original bootmgfw.efi file and any timestamp related metadata are restored to hide that the file has been tampered with.

3.2. Heap

A heap is also allocated using UEFI boot_services!AllocatePages (so it is 4kB aligned, rather than using boot_services!AllocatePool which does not guarantee that alignment).

This heap is used for allocating:

- The hyperv-attachment runtime image buffer (then the hyperv-attachment file is deleted from disk as soon as it has been loaded into memory).

- The PML4 and PDPT for the identity map which is later used.

- The hyperv-attachment’s internal heap.

All of this memory is later hidden from the guest by pointing each page in guest SLAT mappings to a dummy page.

3.3. Starting bootmgfw.efi

The original bootmgfw.efi image is then loaded through UEFI boot_services!LoadImage. A hook on bootmgfw.efi!ImgpLoadPEImage (a routine which loads a portable executable image) is applied. bootmgfw.efi is started using UEFI boot_services!StartImage.

3.4. winload.efi

Once the winload.efi image is being loaded by bootmgfw.efi, it is intercepted by the bootmgfw.efi!ImgpLoadPEImage hook. The bootmgfw.efi hooks are then fully removed before applying a hook to winload.efi!ImgpLoadPEImage. This winload.efi!ImgpLoadPEImage hook allows the loading of hvloader.dll to be intercepted once winload.efi loads it.

3.5. hvloader.dll & Hyper-V launch

Once the loading of hvloader.dll is intercepted via the winload.efi!ImgpLoadPEImage hook, a hook is applied deep in the Hyper-V launch routine within hvloader.dll after removing the hooks on winload.efi. Below is a stripped down decompilation of the Hyper-V launch routine that is hooked (it is called within hvloader.dll!HvlLaunchHypervisor):

1

2

3

4

5

void __fastcall hv_launch(std::uint64_t hyperv_cr3, std::uint8_t* hyperv_entry_point, std::uint8_t* entry_point_gadget, std::uint64_t guest_kernel_cr3)

{

__writecr3(guest_kernel_cr3);

__asm { jmp entry_point_gadget }

}

This hooked Hyper-V launch routine will jump to a gadget which will end up in Hyper-V’s entry point. The parameters are as follows:

- rcx = a CR3 which Hyper-V copies certain PML4es from.

- rdx = the virtual address of the relocated Hyper-V’s entry point.

- r8 = the address of the gadget which jumps to Hyper-V’s entry point.

- r9 = the guest’s kernel CR3 (e.g. 0x1AE000 on Windows 11 24H2).

3.5.1. Loading hyperv-attachment

Continuing with the hook, a PML4e is inserted into the CR3 held in rcx. This PML4e contains an identity map of host physical memory. The physical memory backing the hyperv-attachment is also mapped in by this identity map, so there is a valid virtual mapping of the hyperv-attachment in Hyper-V’s address space. The loaded hyperv-attachment image is relocated by (virtual base of the PML4e/identity map + physical base address of hyperv-attachment image). This relocation means that the hyperv-attachment will be able to execute under Hyper-V’s address space once it is launched.

As @Iraq1337 described in his post, there are a few copies of Hyper-V in physical memory which are not SLAT protected (the guest can read them). Only the final Hyper-V image buffer is hidden from the guest. In the hypervisor launch hook, rdx holds a virtual address backing the final image buffer, which WILL be SLAT protected, so patches can be applied to it without them being disclosed to the guest. In the launch routine hook, a hook is placed on Hyper-V’s VM exit handler, pointing it to a code cave where a far/long jump instruction will detour to the hyperv-attachment’s VM exit handler. All of this is done after the Hyper-V launch routine hook is removed.

4. hyperv-attachment/post Hyper-V launch info

4.1. How does it support different architectures?

The hyperv-attachment supports both Intel and AMD. This is possible through some abstraction of architecture-specific code and a few #ifdefs, meaning both architectures are supported in the same codebase. The steps to compile the hyperv-attachment for Intel or AMD are described in ‘7. How to compile / use’.

4.2. Entry point (pre Hyper-V launch)

The hyperv-attachment’s entry point is called in the Hyper-V launch detour and does the following:

- Sets up a heap manager.

- Sets up initial SLAT context allocations.

- Sets up processor state logs context.

- Intakes some info from the uefi-boot image module for later usage (e.g. the physical base address and size of the uefi-boot image).

Host (the hypervisor running on the hardware which controls the guest) physical memory is accessed by the hyperv-attachment through the identity map that was set up before.

4.3. First VM exit

In the first VM exit, the hyperv-attachment does the following:

- Sets up a NMI (non maskable interrupt) handler in Hyper-V’s global IDT (interrupt descriptor table).

- Sets up the APIC (Advanced Programmable Interrupt Controller), which is later used to fire NMIs to all host logical processors to synchronize SLAT caches.

- Nulls out the uefi-boot image to prevent the guest from searching for it.

Some processes cannot be done in the first VM exit (especially ones relating to SLAT), as Hyper-V has not fully finished initializing yet. After a certain amount of VM exits have taken place, the hyperv-attachment hides the heap (the one that was set up originally in the uefi-boot image) via SLAT. The hidden uefi-boot heap memory includes hyperv-attachment’s internal heap, image allocation and identity map page table structures that were allocated. This is achieved by setting the page frame numbers of all the page table entries to that of a free dummy page in the heap.

4.4. APIC

At the first VM exit, basic information of APIC is fetched through the ‘APIC base’ located at the MSR 0x1B. If APIC is already enabled, then it is checked whether xAPIC or x2APIC is used. If APIC is not already enabled, then the highest possible version of APIC is enabled. For xAPIC, the ICR (interrupt command register) can be accessed through its host physical address at the Local APIC. For x2APIC, the ICR is accessed through the MSRs representing the Local APIC.

Through the ICR, commands can be sent to the Local APIC. This is later used to send Non Maskable Interrupts to all processors but the currently executing one by formulating an ICR request. Later on in the post, it is described how those NMIs are used for synchronizing SLAT code hooks (EPT/NPT hooks). The APIC library which was internally developed for this project and released separately can be found here.

4.5. SLAT

A SLAT CR3 is a CR3 which describes SLAT/translations of guest physical memory to host physical memory.

The SLAT code hooks were implemented as follows:

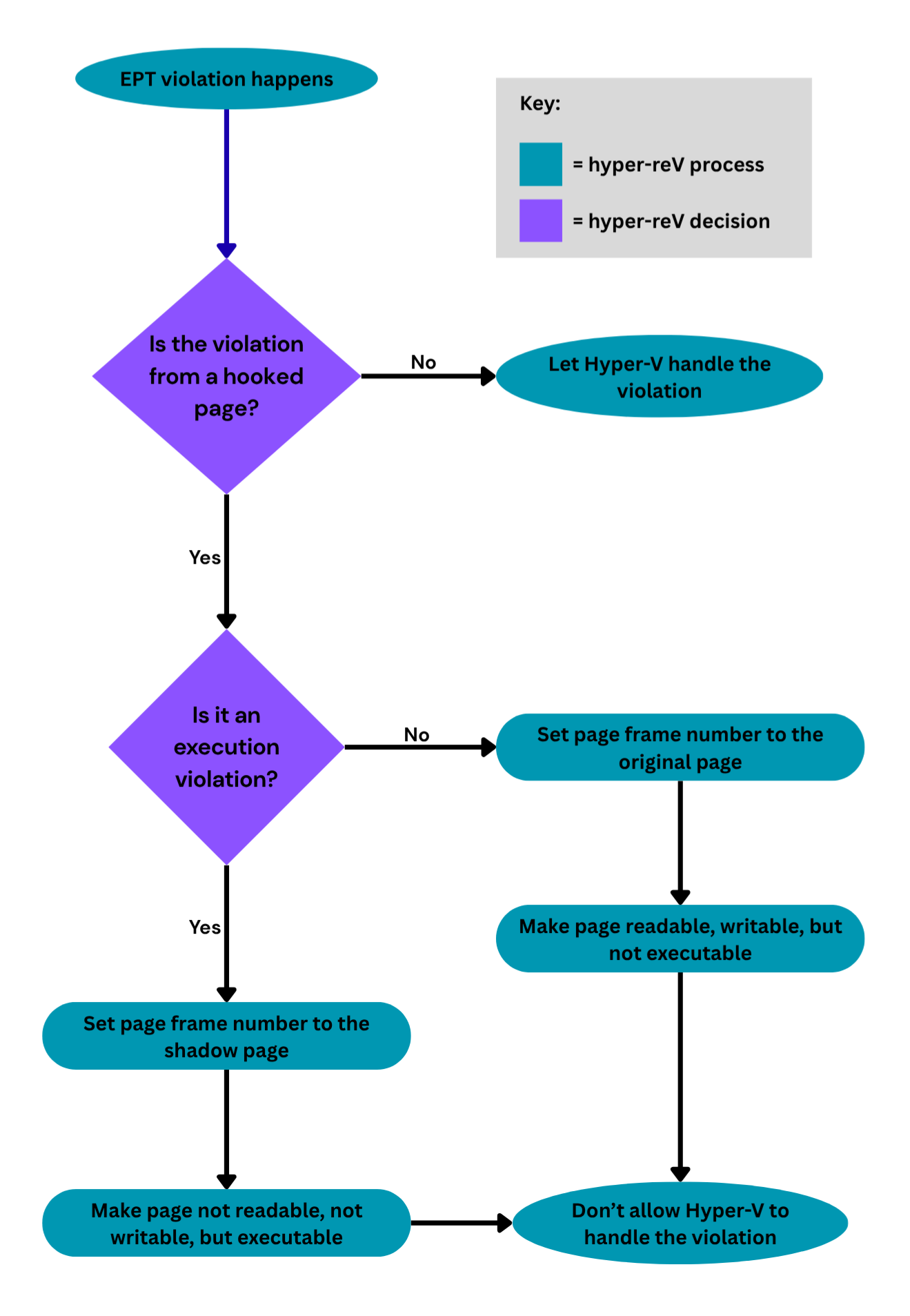

4.5.1. Code hooks on Intel

There is only 1 EPT pointer (Intel’s SLAT CR3), shared by all logical processors in Hyper-V.

The access permissions of the target page to hook to are set –x (non readable, non writable, but is executable) and the page frame number to that of the shadow page (the page which is used for execution with its contents concealed from the guest).

If a read or write occurs in the guest to the hooked page, an EPT violation will be raised. In the EPT violation handler, the original page frame number is restored and the permissions are set to rw- (is readable, is writable, but is non executable).

In case of execution of the page again, these changes are reverted and vice versa.

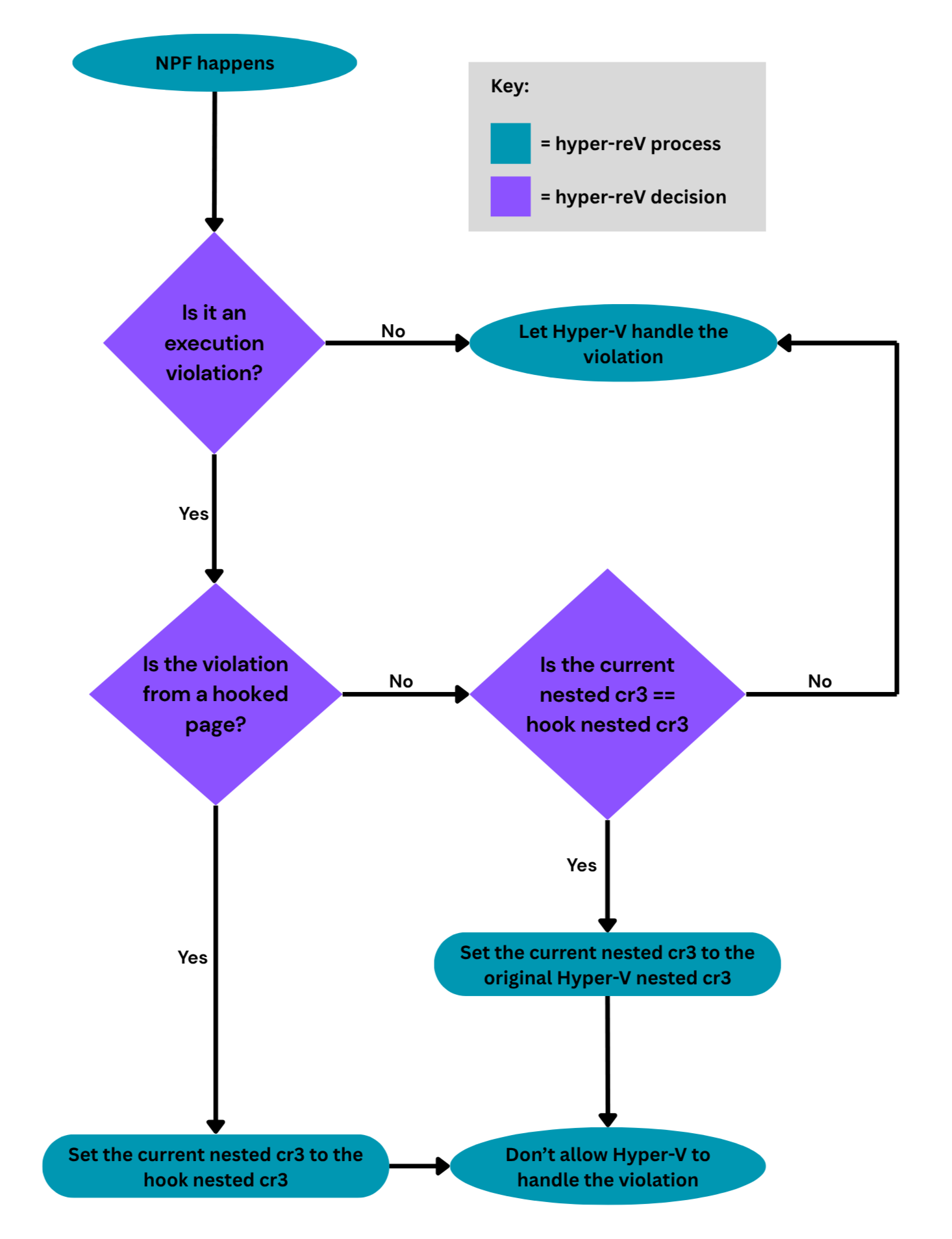

4.5.2. Code hooks on AMD

AMD’s SLAT implementation is called NPT.

Although Hyper-V shares one nested CR3 (AMD’s SLAT CR3 which is similar to Intel’s EPT pointer) over all logical processors, due there being no ability to have execute only pages on AMD, the implementation is vastly different.

As there is no ‘read access’ bit in the page table entries, execute-only pages are not possible in AMD through NPT. So in the first VM exit, an identity map of host physical memory is created (mapped in 2mB large PDes), which is nearly a copy of the Hyper-V nested CR3. This identity map will be known as the hook nested CR3, as it will describe what physical pages the guest can access when it is executing a hooked page.

In the hook nested CR3, all non-hooked pages are set as non executable, meaning it can only execute the pages that are hooked.

When a hook is added, the following happens to the target page:

- The page is set to non-executable in the Hyper-V nested CR3 (so it CAN NOT execute under the Hyper-V nested CR3).

- In the hook nested CR3 the page is made executable (so it CAN execute under the hook nested CR3).

- In the hook nested CR3 the page frame number is set to that of the shadow page.

When the hooked page is executed under the Hyper-V nested CR3, a nested page fault is raised as the hooked page is non executable in that nested CR3. In the nested page fault handler, the nested CR3 is set to the hook nested CR3. When execution is returned to the guest, the hooked page is now executable (and executing the shadow page with the ‘hidden contents’).

Once execution reaches a non-hooked page when under the hook nested CR3 (signaled by a nested page fault caused by execution of any non-hooked page), the nested CR3 is reverted to the Hyper-V nested CR3 and execution can continue as normal until a hooked page is executed again.

When a page is hooked, the page before and after the target page are set to be executable in the hook nested CR3. This prevents issues where there are instructions split over the page boundary of a hooked page (as suggested by @papstuc).

To get the VMCB, @Iraq1337 gave example code of how he does it and the setting up of the hook nested CR3. He also explained the logic behind NPT hooks.

4.5.3. Code hook features common to both AMD and Intel

4.5.3.1. Page split/merge

If a large page has to be split (PDe or PDPTe), to be able to get a PTe to represent the target 4kB guest physical page to hook, those entries are merged back together when the hook is removed (if no other hooks are in that merge range).

This is done to save some heap memory that was used to allocate those lower paging structures and it also improves SLAT performance. The hook_entry_t linked list structure which is used to describe a SLAT code hook fits in just 16 bytes, allowing 256 EPT/NPT hooks to be described in just 4kB.

4.5.3.2. Synchronization using NMIs

APIC is used to send NMIs to all host logical processors to invalidate SLAT caches. This is paired with a bitmap signaling what logical processors need to invalidate their caches. This was done as there was an issue with synchronization of hooks (where @papstuc suggested to synchronize the SLAT caches). Once a logical processor receives the NMI, the following will happen depending on if the processor was in host or guest state:

4.5.3.2.1. NMIs in host state

If the processor was in host state when the NMI hit the processor, it will be delivered to the handler described in the IDT of the host. In the interrupt entry, all general purpose and XMM registers are saved on the stack before calling the NMI processor function. The NMI processor function clears the SLAT cache if it was signaled to be cleared in the bitmap.

The reason why the SLAT cache is not always cleared in every NMI is because Hyper-V uses NMIs for inter processor communication. That is why there is a bitmap which signals if a logical processor still requires a cache flush.

Once the NMI processor returns, all of the general purpose and XMM registers are restored to their original values. After this, the hyperv-attachment’s NMI handler jumps to the original NMI handler that Hyper-V had set up in the IDT (or return from the interrupt directly if there was no handler set up by Hyper-V for some reason).

Host NMIs are not currently handled in AMD, but it makes little difference as there are many frequent guest NMI exits which the hyperv-attachment can use to flush the SLAT cache. Intel handles both host and guest-exiting NMIs.

4.5.3.2.2. NMIs in guest state

If the processor was in a guest state when the NMI hit the processor, the guest will VM exit with a reason of a ‘physical NMI’ and the same NMI processor function is called from the VM exit handler with no need to preserve registers.

4.6. Returning execution to Hyper-V

If a VM exit is not handled by the hyperv-attachment, execution is transferred to Hyper-V’s original VM exit handler.

4.7. Hypercalls

The hyperv-attachment exposes hypercalls for the guest to make. The project monitors the usage of the CPUID instruction to process hypercalls from the guest. When the execution of a CPUID instruction happens in the guest, a VM exit occurs. In its CPUID handler, the hyperv-attachment checks if it is a valid hypercall coming from hyper-reV (through some unique values in registers). If it is not a valid hypercall coming from hyper-reV, execution is returned to Hyper-V (as mentioned in 4.6).

4.7.1. Hypercalls list & descriptions

guest_physical_memory_operation - read / write guest physical memory guest_virtual_memory_operation - read / write guest virtual memory translate_guest_virtual_address - translate a guest virtual address to a guest physical address read_guest_cr3 - get the current guest CR3 add_slat_code_hook - add a SLAT code hook remove_slat_code_hook - remove a SLAT code hook hide_guest_physical_page - hide a guest physical page from the guest log_current_state - log the current processor state in a trap frame, logs can be flushed later flush_logs - flush all the logs to a guest virtual buffer get_heap_free_page_count - get the amount of free pages left in hyperv-attachment’s heap

5. Avoiding detection

One of the main goals of this project is to avoid the detection vectors that other similar projects have. By allocating the hyperv-attachment independently from the Hyper-V image, the project evades the detection of memory allocations located after the Hyper-V image allocation being shifted by the size of the inserted image.

In addition, the project only applies hooks to the final Hyper-V image protected by SLAT. This avoids the detection of a guest searching for copies of the Hyper-V image (e.g. one from when it is initially loaded from disk) which are not protected by SLAT. Furthermore, bootmgfw.efi’s (Windows’ bootloader which is replaced prior to boot with the uefi-boot.efi module) original file metadata (e.g. time modified) is restored to hide that it has been tampered with.

6. Usermode app information

The usermode app serves as a kernel debugger, as well as an example of what can be achieved with the project’s capabilities. It has many ‘commands’ you may execute through the command line interface. The app uses CLI11 for command parsing.

6.1. Command usages and descriptions list

rgpm - reads memory from a given guest physical address. Usage: rgpm physical_address size

wgpm - writes memory to a given guest physical address Usage: wgpm physical_address value size

cgpm - copies memory from a given source to a destination (guest physical addresses) Usage: cgpm destination_physical_address source_physical_address size

gvat - translates a guest virtual address to its corresponding guest physical address, with the given guest CR3 value Usage: gvat virtual_address CR3

rgvm - reads memory from a given guest virtual address (when given the corresponding guest CR3 value) Usage: rgvm virtual_address CR3 size

wgvm - writes memory from a given guest virtual address (when given the corresponding guest CR3 value) Usage: wgvm virtual_address CR3 value size

cgvm - copies memory from a given source to a destination (guest virtual addresses) (when given the corresponding guest CR3 values) Usage: cgvm destination_virtual_address destination_CR3 source_virtual_address source_CR3 size

akh - add a hook on specified kernel code (given the guest virtual address) (asmbytes in form: 0xE8 0x12 0x23 0x34 0x45) Usage: akh [OPTIONS] virtual_address Example: akh ntoskrnl.exe!PsLookupProcessByProcessId –monitor –asmbytes 0x90 0x90 –post_original_asmbytes 0x90 Options: –asmbytes –post_original_asmbytes –monitor

rkh - remove a previously placed hook on specified kernel code (given the guest virtual address) Usage: rkh virtual_address

gva - get the numerical value of an alias Usage: gva alias_name

hgpp - hide a physical page’s real contents from the guest Usage: hgpp physical_address

fl - flush trap frame logs from hooks Usage: fl

hfpc - get hyperv-attachment’s heap free page count Usage: hfpc

lkm - print list of loaded kernel modules Usage: lkm

kme - list the exports of a loaded kernel module (when given the name) Usage: kme module_name

dkm - dump kernel module to a file on disk Usage: dkm module_name output_directory

6.2. Kernel hooks

On startup, the app finds a suitable page in ntoskrnl.exe (the main Windows kernel image) to use as the ‘detour holder’. This is where the original bytes of the hooked routine that have been overwritten by the inline hook on the shadow page will reside.

By using a pre-existing page, a new kernel executable page does not have to be allocated (which would have been suspicious to some security tools had an unknown kernel page being caught executing). This page is SLAT hooked so the executable contents will be hidden from the guest.

This page from ntoskrnl.exe might not typically be executed, so it may be wiser to load an unused kernel driver that will not be actively executing, and use a random page from its .text section as the detour holder instead.

Utilizing SLAT code hooks, kernel routines can be hooked with the usermode app. This is done by applying an inline hook on the shadow page, which then jumps to a location holding the original bytes, a typical detour.

The command allows the user to specify some assembly (in hex form) to be executed either before/after the original bytes execute (via –asmbytes / –post_original_asmbytes in command arguments), as well as making the hooked routine log the processor state whenever it is executed (via –monitor in the command arguments).

Unlike most other hypervisor assisted debuggers, this project fully resolves rip relative operands to their absolute values. This means that the user can place hooks on a routine where the original bytes have rip relative operands (e.g. jz 50 or relative call/jmp to a routine). This also resolves rip relative memory accesses (e.g. cmp [rip+x], 0).

6.3. Command aliases

The usermode app also parses all loaded kernel modules, so the user can reference a module’s exports or base address by name (e.g. ntoskrnl.exe!PsLookupProcessByProcessId or ntoskrnl.exe). In addition, the current CR3 that the process executes under can be referenced using ‘current_cr3’.

6.4. Flushing logs

The logs capture general purpose registers (from rax-r15), the rip, the CR3, and a snapshot of the stack.

These logs are generated by placing the ‘–monitor’ flag on the kernel hook command. This way, when the hook is executed, it calls to the hypervisor to log the processor state each time. When the logs are flushed using the ‘fl’ / flush logs command in the usermode app, it looks as follows:

- rip=0xFFFFF8049B0BA5E6 rax=0x3 rcx=0x538 rdx=0xFFFFAF869BF2F260 rbx=0x0 rsp=0xFFFFAF869BF2F208 rbp=0xFFFFAF869BF2F360 rsi=0x80 rdi=0x538 r8=0xFFFFAF869BF2F5A0 r9=0xFFFFE486C68FA800 r10=0xFFFFF8049B0BA5E0 r11=0xFFFFAF869BF2F458 r12=0xFFFFF8042D693000 r13=0xFFFFE486CD91E000 r14=0xFFFFAF869BF2F2A8 r15=0x0 CR3=0x1B473C000

stack data: 0xFFFFF8042D6A7724 0x0 0x8 0xFFFF3B4D56ACD14A 0x0

7. How to compile / use

7.1. ‘uefi-boot’ compilation

To compile the uefi-boot module, you must install NASM (https://nasm.us) and “check that the environment variable NASM_PREFIX is correctly set to NASM installation path” (quoted from https://github.com/ionescu007/VisualUefi/#Installation).

All submodules must be cloned (VisualUEFI / EDK2). They will reside in uefi-boot\ext.

The command to clone the repository (including submodules):

1

git clone --recurse-submodules https://github.com/noahware/hyper-reV.git

In addition, you must build the EDK2 libraries by opening uefi-boot\ext\edk2\build\EDK-II.sln and building the entire solution.

7.2. Architecture-specific compilation

The hyperv-attachment must be selected to be built for either Intel or AMD.

To compile the hyperv-attachment for Intel: #define _INTELMACHINE in arch_config.h (which is in the hyperv-attachment src directory).

To compile for AMD, simply comment that aforementioned #define line out and rebuild.

The binaries of the uefi-boot module and usermode app will work for both Intel and AMD no matter the configuration specified in the hyperv-attachment.

7.3. Load script

There is a script (‘load-hyper-reV.bat’) in the root directory of the project which will place the uefi-boot module and the hyperv-attachment in the EFI partition when ran as administrator in the same directory as the uefi-boot.efi and the hyperv-attachment.dll files. Once you run this, hyper-reV will load at the next boot.

7.4. Usage with Secure Boot

To load the project with secure boot enabled, a vulnerable bootloader could be exploited, as described in this post.

7.5. Usage with TPM

If evading an advanced security tool, it is not recommend to run the project with TPM enabled if the security tool performs boot attestation. This is because it can see that the uefi-boot binary was loaded (through info stored in the TPM PCRs or through measured boot logs). This paragraph’s information is from Zepta’s post.

8. Source code

The source code can be found on this GitHub repository.

9. Tested Windows versions

The project has been tested on the following versions on both Intel and AMD:

Windows 10 21H2, Windows 10 22H2, Windows 11 22H2, Windows 11 23H2, Windows 11 24H2.

Ensure the latest minor updates for those major Windows versions are applied if the project does not work. The system must also be able to run Hyper-V.

10. Credits

John / @Iraq1337 - invaluable advice, especially with AMD theory, examples of nested CR3 identity mapping and a way to get the VMCB. In addition, he also suggested to apply patches to Hyper-V right before it launches.

@papstuc - crucial advice, especially for the suggestion of synchronizing EPT/NPT cache across all processors, his idea for AMD NPT hooks on page splits and his Windows file format parsing library used in the usermode app.

mylostchristmas - found that the prior method of allocating SLAT protected SLAB pages via winload.efi’s SLAB allocator did not function the same way on 24H2. This functionality was then removed from the project and replaced with in-house SLAT protection.